A Quick History

What is a Luddite?

THE Luddites, armed with hammers, pistols and a desperation to protect their livelihoods, seized the imagination of the British public in the early-nineteenth century. And they have held on to it. Two centuries later, the word 'Luddite' is still familiar all round the English-speaking world, even if not fully understood.

Were the Luddites simply a band of destructive men who seriously thought that by smashing the new machines in the factories of the early 1800s they could 'uninvent' the technology that threatened to take away their jobs and their social status as elite craftsmen? That is how they are often seen today, and the word 'Luddite' is used for anybody who is reluctant to use a computer or a mobile phone!

But there was more to the original Luddites. Perhaps violent protest was the only way they could exert any control over the changes taking place in their industries. Perhaps Luddism should be seen as a drastic form of collective bargaining. Perhaps some Luddites were fired by the radical ideas thrown up in the wake of the French Revolution. And what role was played by the economic hardships that accompanied Britain’s long war with Napoleonic France?

These are some of the issues that commentators and historians have debated for 200 years. And the bicentenary of the central drama in the Luddite saga is an ideal time for a fresh appraisal.

The drama and tragedy of West Riding Luddism

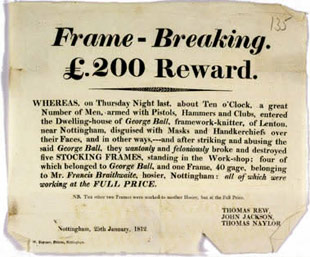

Machine breaking as a form of protest had been happening in England since at least the late-seventeenth century. It gained momentum in the 1790s and again in the early 1800s, when framework knitters in Nottingham, angry at the prospect of wage cuts, took hammers to their machines. They remembered the name of a Leicestershire lad, named Ludlam maybe, who had smashed a machine in a fit of pique, and from him came the semi-mythical figure of General Ludd, in whose name the protests were said to take place.

Machine-breaking also spread to the cotton industry of Lancashire and Cheshire, but it was in Yorkshire that the most disturbing and ultimately poignant drama was played out. The violent events of 1812 in the West Riding, leading to a string of executions in January 1813, have been told and retold ever since by historians, novelists and playwrights.

Cropper lads

The key characters in West Riding Luddism were tradesmen known as croppers, who needed great skill and strength to manipulate enormous shears with which they smoothed the surface of the woollen cloth produced in the weavers' cottages that dotted the hills and villages.

But a machine had been invented that could shear cloth much more efficiently and some of the new breed of Yorkshire manufacturers were installing this latest technology in their new-fangled factories, which were bringing all the processes of cloth production under one roof.

Faced with the loss of their craft, their status – and their high wages – the croppers and other textile craftsmen of the West Riding took drastic action in 1812…

Enoch shall break 'em!

In January there was a serious arson attack on a mill in Leeds. The next month saw the ambush and destruction of shearing frames destined for Rawfolds Mill, near Cleckheaton. Meanwhile, in the Huddersfield area there were at least 13 machine-breaking incidents and many late-night raids by large bands of armed men. For example, on 15 March, men with blackened faces attacked the Taylor Hill premises of manufacturer Francis Vickerman.

April 9 saw a massive attack on Foster’s Mill at Horbury and cropping frames made by the Marsden company run by Enoch Taylor were smashed – using sledgehammers produced by the same firm! Hence the Luddite slogan, 'Enoch hath made them, Enoch shall break them'.

The Luddites were causing fear and consternation among the mill-owners of the West Riding, although they might have had the support of many members of the general public. Then the tide turned…

The Battle of Rawfolds

On 11 April, more than 100 Luddites gathered at the Dumb Steeple, still a landmark near Mirfield. At the dead of night they marched on Rawfolds Mill. But its owner, William Cartwright was ready for them. The mill was fortified and soldiers were stationed there. The Luddites were beaten off and two of them were killed.

This led to a change in tactics, including raids on houses, in search of money and weapons. And on 28 April, the manufacturer William Horsfall was shot dead in an ambush at Crosland Moor as he rode back from Huddersfield to Marsden.

Horsfall had proclaimed that he would ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood – but it was his blood that was shed and led to the downfall of the West Riding Luddites.

Radcliffe's army

The authorities, led by the energetic Huddersfield magistrate Joseph Radcliffe, stepped up their investigations. Hundreds of troops were called in and it would have seemed that the area was under martial law while the hunt for Horsfall’s killers gathered pace.

Eventually, a man named Benjamin Walker came forward and confessed to having taken part in the murder, along with William Thorpe, Thomas Smith and George Mellor, a charismatic cropper sometimes dubbed '“the General Ludd of Yorkshire'.

By turning King’s evidence, Walker saved his own skin. But the other three were tried and hung in York, in January 1813. Eight days later, 14 other men were hanged, after being rounded up for their part in the Rawfolds Mill attack.

Those are the bare bones of a violent but complex and thought-provoking saga that still intrigues historians, not least because the evidence for Luddism is fragmentary and difficult to interpret. After all, machine breaking was a capital offence, so ex-Luddites kept quiet about their role!

Visit the Luddite Link to learn more about the many dimensions of a story that symbolises the painful birth pangs of the industrial age and which still has relevance today.

Did You Know?

- Some accounts of Luddite raids have the men dressing as women, to disguise themselves. Later in the century, the 'Rebecca Riots' in Wales, protesting against turnpike gates, also featured cross-dressing men.

- When 64 Luddites were placed in the dock at York in 1813, there were 24 men from the Huddersfield area, all of them croppers, with an average age of 27.

- Luddites who avoided arrest dare not speak about their involvement, but in the 1870s, when they would have been very old men, they began to whisper some of their secrets to local historians. This is sometimes called 'the hidden history of Luddism'.

- George Walker's well-known illustrated book 'The Costume of Yorkshire', published in 1814, has a picture showing croppers in their workshop and the text makes reference to 'the late unhappy disturbances' and 'the prompt execution of some of the ringleaders'.

- The dramatic events of 1812-1813 in Yorkshire have been the basis of many novels, since Charlotte Bronte's 'Shirley' in 1848. An unlikely entry into the sequence was 'Through the Fray', written in 1885 by G.A. Henty, best known for his tales of derring-do in the overseas Empire.

- Twentieth-century Halifax author Phyllis Bentley's epic novel of 1931, 'Inheritance', begins with the Luddite riots. It was made into a 10-episode ITV drama in 1967. Among the stars were John Thaw and James Bolam.

- Croppers worked hard, manipulating their enormous shears, but they also played hard and often gained a bad reputation. In 1814 George Walker wrote that 'the majority are idle and dissolute, owing perhaps partly to the laborious nature of their occupation, which too often induces habits of drunkenness...'

- Wellington's army in the Peninsular was smaller in number than the 12,000 troops assigned to deal with Luddite disturbances in 1812. In Huddersfield alone, 1,000 troops were stationed.

- Lord Byron was the Luddites' friend! For his maiden speech in the House in of Lords, in February 1812, he denounced a new law to make frame-breaking punishable by death and urged greater understanding of the plight of people thrown out of work by new machinery. His speech caused a sensation but he failed to halt the legislation.

- As a young man, George Mellor - sometimes called the General Ludd of Yorkshire - might have visited Russia and brought back with him the long-barrelled pistol that he used to gun down the mill owner William Horsfall.

- The 1830s saw a rural equivalent to Luddism, when agricultural workers in the South of England smashed threshing machines and torched haystacks. Their answer to General Ludd was the mythical Captain Swing.

- In the late-1990s there was a neo-Luddite movement in the USA, opposed to globalisation. In 1996 a 'Second Luddite Congress' was held in Ohio.

- Joseph Radcliffe, the Milnsbridge magistrate who was energetic in the pursuit and interrogation of Luddites, earned a baronetcy for his efforts but he was deeply unpopular on his home patch.

- The headquarters of West Riding Luddism was said to be the finishing, or cropping shop of John Wood at Longroyd Bridge, near Huddersfield, although the proprietor claimed ignorance of any plots being laid. One of the employees was his stepson, George Mellor, alias the General Ludd of Yorkshire.

- How to spot a cropper and a potential Luddite: The painful process of learning to manipulate the heavy shears led to the wrists becoming calloused, or "hooved."

- When a man took the Luddite oath, the process was known as "twisting in." The fearsome language of the oath stated that the penalty for giving away Luddite secrets would be "sent out of the world by the first brother who shall meet me, and my name and character blotted out of existence and never to be remembered but with contempt and abhorrence."

- A Yorkshire legend had it that croppers were such a wild, drunken bunch that when they all ended up in hell the Devil was desperate to get rid of them. So he opened the gates again and shouted "Ale! Ale!". The croppers rushed out and the Devil bolted the gates of hell after them...

- The St Crispin Inn in Halifax was the meeting place for radicals who made common cause with the Luddites. They included the elderly John Baines who would be sentenced to seven years transportation for administering an illegal oath. The folk museum at Shibden Hall, Halifax, has a reconstruction of the St Crispin Inn which is open to visitors.